Past Issues

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream

- Our Great Tchaikovsky

- Heartbreak House

- The Absolute Brightness of Leonard Pelkey

- Cloud 9

- The Comedy of Errors

- A Christmas Carol

- The Piano Lesson

- Queens for a Year

- Anastasia

- Having Our Say

- Romeo & Juliet

- The Body of an American

- A Christmas Carol (2015)

- Rear Window

- An Opening in Time

- Kiss Me, Kate

- The Pianist of Willesden Lane

- Reverberation

- Private Lives

- A Christmas Carol (2014)

- Hamlet

- Ether Dome

Meet the Artist: A Conversation with Mia Dillon

By Theresa MacNaughton, Community Engagement Associate

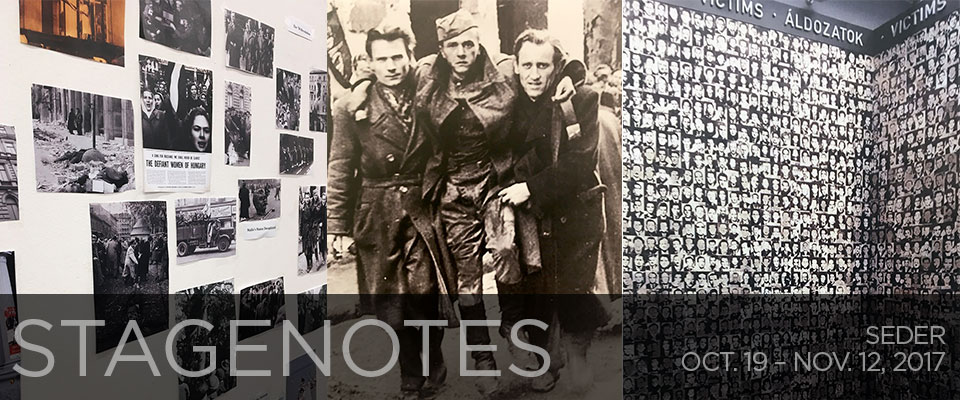

Seder marks Mia Dillon’s return to Hartford Stage. In the world premiere play by Sarah Gancher, Dillon portrays Erzsike, a mother with a mysterious past working for the AVO, Hungary’s KGB, who seeks to reconcile with her eldest daughter. As her family prepares to celebrate its first Passover Seder, a lifetime of dark secrets is revealed as Erzsike confronts the ghosts from her past.

Seder marks Mia Dillon’s return to Hartford Stage. In the world premiere play by Sarah Gancher, Dillon portrays Erzsike, a mother with a mysterious past working for the AVO, Hungary’s KGB, who seeks to reconcile with her eldest daughter. As her family prepares to celebrate its first Passover Seder, a lifetime of dark secrets is revealed as Erzsike confronts the ghosts from her past.

Mia Dillon first appeared at Hartford Stage in Noël Coward’s bittersweet A Song at Twilight in 2014 and returned last season with a Connecticut Critics Circle award-winning turn as Edward and Betty in Caryl Churchill’s Cloud 9. The Tony Award-nominated actor has appeared on Broadway in Our Town (with Paul Newman), Crimes of the Heart and Agnes of God. Her regional theatre credits include On Golden Pond, Arsenic and Old Lace, and Cat on A Hot Tin Roof. Dillon spoke with Hartford Stage about Seder and the complexity of her character, Erzsike.

What speaks to you about Sarah Gancher’s play, Seder?

The play speaks to me on so many levels because it is such a rich, complex play. The heart of it is the family dynamic, which anyone who has been a parent, or had a parent can relate to. The conflict and comedy that comes along with trying to hold a family meal with sparring participants holding opposing political views will certainly resonate with today’s audiences. But layered in with that is the setting of the play, in Hungary. I love history and have really appreciated the books I’ve read as research for this part. Love is at the heart of this play for me – Erzsike’s love for her daughter, Judit, as well as the lies that are told and sacrifices made in order to survive.

Tell us about your character, Erzsike, in Seder. What have you learned so far from her?

She is a survivor. She loves her children. She makes mistakes but as she says, “I did what anybody does. I did the best I could.” The evening of the Seder raises a lot of questions for her. She protests her innocence, “I didn’t know about any torturing or killing. I never saw anything myself. I had children. I had to go along. I had to protect you.” Hopefully, the audience will resonate with her journey and the difficult life choices she has had to make.

How often have you had the opportunity to originate a character? Do you approach the process any differently than when you perform in a revival?

It is an absolute luxury to originate a character when you have a playwright in the room answering questions. Sarah Gancher has very specific ideas about these characters and has been enormously helpful in guiding us to realizing them from the page to the stage, bringing her vision to life. I love working on new plays and have been fortunate in my career to originate some wonderful characters. I also spent six summers at the Eugene O’Neill Playwrights Conference and four summers at the Sundance Institute workshopping new plays. The process as an actor is the same: finding the truth.

Seder is your third show at Hartford Stage – following Cloud 9 last year and A Song at Twilight in 2014. The characters you’ve portrayed – Erzsike, Betty and Hilde – have all experienced significant, transformative events in their lives. Have you found any parallels between these women?

I will probably better be able to answer this looking back on this production. I’m still in the heart of rehearsals, exploring and finding the truth of Erzsike. But, I can say that all three are women who’ve had challenging lives and have had to make compromises in order to survive. The challenges are different, but all three involve complicated relationships with the men in their lives.

In Cloud 9, you played both young Edward and Betty; in Seder, Erzsike’s character ages from 19 to over sixty. As an actor, what draws you to these complicated and layered opportunities?

I’ve done other plays where my character has aged a few years over the course of the play, but none with quite this range! I loved playing Edward in Cloud 9 because I let loose my inner child. Although I have to confess that as a 10-year-old he had more energy than I have. As soon as I ran off stage, I would collapse in a chair and catch my breath, getting ready for the next running entrance.

In Seder the challenge is that I don’t have a change of costume and wig. In an instant, I become my younger self, triggered by something in the current scene. Memories haunt Erzsike. Luckily, the writing brilliantly supports me in this time transport; and with the help of our fabulous director Elizabeth Williamson, it doesn’t seem that hard. Wouldn’t we all like to step back in time to try to gain a better understanding of something in our past that has haunted us?

Seder poses serious philosophical and political questions centered on the moral choices that people make. What do you hope people take away from this new play?

There’s an old Jewish curse, “May you live in interesting times!” Well, like it or not, we live in interesting times. Fortunately, the arts tend to bloom in those eras and we get beautiful plays, like Seder, which is set in Budapest in 2002 after Hungary has undergone the seismic changes of the 20th century. We, as Americans, may not have the extent of political turmoil that has rocked Hungary, but we’re doing a pretty good job of political chaos at the moment.

The most thought-provoking question in the play, for me, is where does personal responsibility stop? Do we intervene when we know something is wrong? My character, Erzsike, says “I didn’t always help, sometimes it was too dangerous.” Do we intervene if it puts our own safety at risk? And how much does ignorance insulate us and relieve us of that responsibility?